By measuring the number of copies of just one gene from cancer DNA circulating in the bloodstream, scientists were able to identify the patients with stomach cancer who were most likely to respond to treatment.

Stomach cancers with many copies of the FGFR2 gene were found to be particularly susceptible to the experimental drug, an FGFR inhibitor, because the tumours had become reliant on, or ‘addicted’ to, the gene in order to grow.

The new test, described in the prestigious journal Cancer Discovery this week, could be used in future to direct treatment, by identifying a subset of patients who could benefit from an FGFR2 inhibitor.

A team at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust assessed the potency of the FGFR inhibitor AZD4547 in patients with stomach and breast cancer in a phase II clinical trial that screened 341 patients.

The study was funded by Cancer Research UK and AstraZeneca, with some additional funding from the charity Breast Cancer Now and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR).

Initially using tumour biopsies, researchers found many copies of the FGFR2 gene in 9 per cent of cancers among the 135 stomach cancer patients on the trial. Cancer cells often undergo changes in their DNA that can result in multiple copies of genes that help cancers grow and spread.

Tumours with multiple copies of the gene FGFR2 responded well to the treatment, with three out of nine patients having a response to treatment, and in those patients the drug worked for an average of 6.6 months.

Some 18 per cent of breast cancers were found to have multiple copies of a sister gene, known as FGFR1, and not FGFR2 – but tumours with multiple FGFR1 genes did not have the same susceptibility to the drug.

Interrogating the reason for their observations, the researchers took samples back to the laboratory to pick apart the reasons why the drug worked well in FGFR2 tumours and not in other FGFR genes.

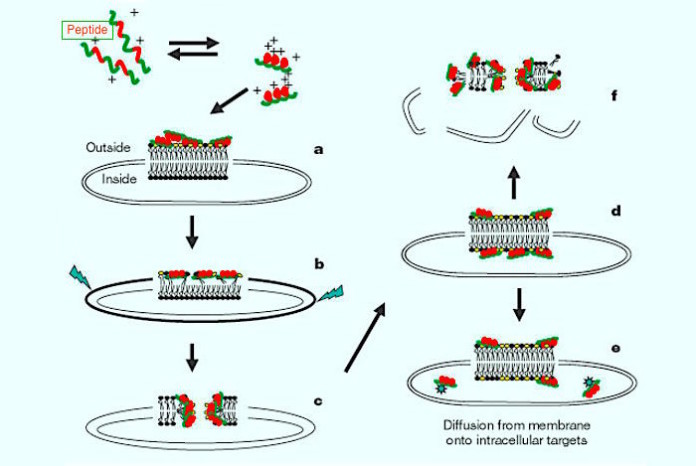

Through painstaking experiments, they found that FGFR2 hijacks molecular pathways that help cancer grow and spread, and some stomach tumours become addicted to high levels of the gene’s protein product.

This phenomenon is known as cancer gene ‘addiction’, and is a weakness that can be exploited by modern targeted therapies.

Study co-leader Dr Nicholas Turner, Team Leader in Molecular Oncology at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, and Consultant Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, said:

“Our study has identified a potential new treatment for a subset of patients with gastric cancer, and has explained why some gastric cancers were responding to treatment while others did not. We were able to design a blood test to screen for patients who were most likely to benefit from an FGFR2 inhibitor, helping us to target drug therapy at those patients who were most likely to benefit.

“The research helps shed light on how tumours can become addicted to certain cancer genes, and shows how we can treat the disease effectively by taking advantage of these weak points in cancer’s armoury.”

Professor David Cunningham, Consultant Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and Honorary Professor of Cancer Medicine at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, who was Chief Investigator of the clinical trial associated with the study, said:

“This is a great example of a faster, smarter treatment being delivered to a relatively small but important group of patients with gastric cancer, made possible through the support of our NIHR Biomedical Research Centre.”

Professor Paul Workman, Chief Executive of The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said:

“This is an important study, which shows how new targeted treatments can exploit cancer’s genetic addictions, and acts as a proof of principle that cancer DNA detected in the bloodstream can be used to guide treatment.

“This is a perfect example of not just bench to bedside but back again – showing the value in taking clinical findings and scrutinising them back in the lab.”

Dr Emma Smith, Cancer Research UK’s science information manager, said:

“Developing ways to identify people who are most likely to benefit from drugs targeting particular genetic faults is vital to help ensure each patient gets the most effective treatment. The next steps will be larger clinical trials to see if testing for this genetic abnormality can spot people whose stomach cancer will respond well to this treatment.”

Dr Carl Barrett, VP Translational Science, Oncology iMed, Innovative Medicines & Early Development, AstraZeneca, said:

“This collaboration illustrates the importance of carefully analysing patient tissue samples to develop an understanding of markers of sensitivity and resistance. This knowledge will help future development of FGFR inhibitors and the understanding of the genomic response to treatment. The development of a blood-based biomarker assay, which will detect circulating tumour DNA, will help identify patients whose tumour is addicted to FGFR2 gene amplification events. AstraZeneca already uses this approach for several targeted therapies across our oncology portfolio.”

Source: ICR