Now, it would seem, investigators at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute are looking to take the lead in this critical discussion because they have recently published data on the discovery of a new type of immune antibody that can evolve rapidly to neutralize a broad range of influenza virus strains—including those the body hasn’t yet encountered. The revelation of the body’s ability to make the adaptable antibody suggests potential strategies for creating improved or even universal influenza vaccines.

The new antibody, named mAb 3I14, is a broadly neutralizing antibody (bnAb), so-called because it can recognize and disable a diverse group of the 18 different strains of influenza virus that circulate the globe. The Dana-Farber team reported that the 3I14 antibody demonstrated it could efficiently neutralize the two main types of influenza A virus—groups 1 and 2—and protected mice against lethal doses of the virus.

“We report a haemagglutinin (HA) stem-directed bnAb, 3I14, isolated from human memory B cells, that utilizes a heavy chain encoded by the IGHV3-30 germline gene,” the authors wrote. “MAb 3I14 binds and neutralizes groups 1 and 2 influenza A viruses and protects mice from lethal challenge. Analysis of variable regions of VH [heavy-chain] and VL [light-chain] germline back-mutants reveals binding to H3 and H1 but not H5, which supports the critical role of somatic hypermutation in broadening the bnAb response.”

The findings from this study were published recently in Nature Communications in an article entitled “A Broadly Neutralizing Anti-Influenza Antibody Reveals Ongoing Capacity of Haemagglutinin-Specific Memory B Cells to Evolve.”

The 3I14 antibody is made by the human immune system’s memory B cells—immune cells that circulate in the blood and reside within the spleen and bone marrow. When an individual is exposed to an infectious agent or receives a vaccine made from pieces of that agent, B cells respond to the invaders and can generate a memory of the particular type or strain. Pools of these memory B cells constitute a reserve defensive force that can quickly recognize and attack the microbe or virus should it enter the body again.

Unfortunately, influenza’s hypermutability makes it difficult to protect against one-time vaccination strategies. Viral changes occur every flu season and are responsible for the seasonal flu that we are vaccinated against yearly. The more dramatic changes that occur when new viruses emerge from animal and bird reservoirs are responsible for potentially more severe pandemics, such as the deadly H1N1 strain that emerged in 2009.

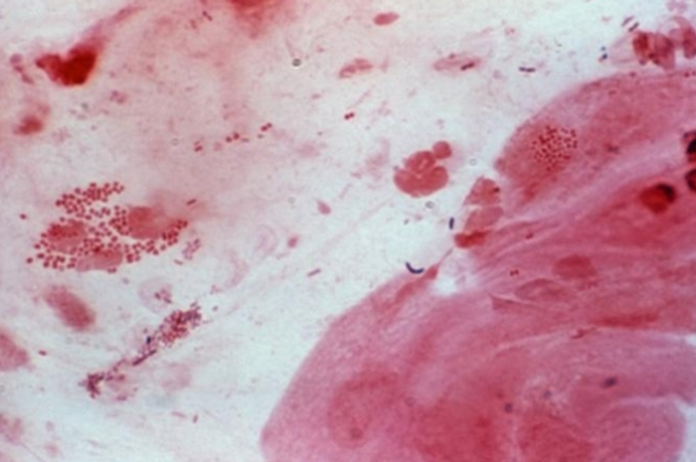

The discovery of the new bnAbs came after senior study investigator Wayne Marasco, M.D., Ph.D., a cancer immunologist and virologist at Dana-Farber, along with his colleagues took blood samples from seven blood bank donors that were shown to harbor these types of antibodies and challenged their immune B cells in the laboratory with an array of flu viruses. The researchers ultimately identified one B-cell population “that recognized all the strains we screened against it,” Dr. Marasco said. Sorting through the B cells’ DNA, the researchers isolated the gene that carried the instructions for creating the 3I14 antibody.

The research team found that the antibody could bind to the unchanging stem portion of flu viruses. Moreover, they reported that the antibody’s genetic makeup gave it the flexibility to adapt or evolve, through mutations, to neutralize a myriad of flu viruses.

To test the antibodies’ full capabilities, the investigators challenged the B cells with a bird flu virus of the H5 type that the immune cells had never encountered. Although the 3I14 antibody didn’t initially bind strongly to the virus, the researchers introduced a single DNA mutation that increased its binding strength to H5 by ten times. “To our delight, we made one mutation, and it did the job,” Dr. Marasco noted. “This was a simple mutation that would readily occur in nature.”

“These data provide evidence that memory B cell evolution can expand the HA subtype specificity,” the authors concluded. “Our results further suggest that establishing an optimized memory B cell pool should be an aim of ‘universal’ influenza vaccine strategies.”

Source: GEN